Andrew Carnegie Helped Jefferson City to Build Its First Free Public Library

1871 – 1899: Getting off the ground

In late May 1871, the Jefferson City People’s Tribune editorialized about the need for a “circulating library” in the capitol city. California, Missouri had established a Library Association that featured a library in a vacant room of the Moniteau County Courthouse. Local residents who wished to use the library paid a two dollar initiation fee and a two dollar annual fee for the privilege. The library was open from 3:00-10:00 p.m. during the winter months only and was staffed by a librarian who was paid $10 per month. “Here congregate” the Tribune noted, “ the young men of town, who in former times were forced into billiard rooms because they had no other place to spend their time.” Jefferson City, the Tribune urged, should follow California’s lead.

Less than two months later, a Jefferson City Library Association was formed on the California model and a “subscription library” was established, although the library was short-lived. Several subsequent attempts at creating a Jefferson City library followed, including one housed in a downtown bookstore and another in the Hope Building, a structure that still stands at the northeast corner of the intersection of Madison and High streets.

These unsuccessful attempts at creating a library notwithstanding, the capital city remained without a library for most of the last two decades of the nineteenth century. Then, in the winter of 1898, 300 subscribers joined together to create a new Jefferson City Library Association which opened a library in the basement of the courthouse on March 1, 1898. A subscription fee of three dollars per year, or 25 cents per month, was charged. The organization hired Miss Adalaide J. Thompson as its librarian. Over the next three years, the library acquired approximately 1,700 volumes through a combination of purchases and donations.

Although the subscription library served at least some of the readers in the Jefferson City community, many people in the capital city wanted to see a free public library established. In the fall of 1899, the Rev. John Fenton Hendy, pastor of the First Presbyterian Church of Jefferson City, and Mr. Arthur M. Hough, a local attorney, began to discuss the idea of asking famous philanthropist Andrew Carnegie for a donation that would allow Jefferson City to build a library that could be opened to the general public without a subscription fee. They both knew that Carnegie began funding grants for free public libraries to local communities in 1881.

1900, Part 1: Carnegie says “Yes”; the city pledges support

Soon, Hendy and Hough drafted a letter to Carnegie that was signed by prominent citizens. Months passed before Carnegie respond early in 1900. Carnegie offered to donate $25,000 to the City of Jefferson under two conditions. First of all, Carnegie wanted the city to purchase on its own a suitable site for the library. Secondly, he wanted the city council to “obligate itself by resolution to expend the sum of three thousand dollars annually, to maintain the library….”

Hendy and Hough were disappointed with Carnegie’s response. They feared that the city council would not commit to spending $3.000 annually to maintain the library. Thus, the two of them traveled to New York, hoping for a personal audience with Carnegie so that they might try to persuade him to reduce the annual commitment to be made by the city. Unable to meet with Carnegie, the men were told by his secretary that the philanthropist would be unyielding and that if the community would not spend $3,000 of the city money for the library’s maintenance, Carnegie would give nothing to the project.

Hendy and Hough returned to Jefferson City and lobbied the city council to commit the funds in accordance with Carnegie’s wishes. The city council decided to propose a tax of one mill on every dollar of assessed valuation, with the money raised to be used for the library maintenance fund. On June 19, 1900, Jefferson City residents went to the polls to vote on this proposition. They approved it overwhelmingly by a vote of 839-42.

1900, Part 2: Approving a location and construction

Soon, Hendy and Hough drafted a letter to Carnegie that was signed by prominent citizens. Months passed before Carnegie respond early in 1900. Carnegie offered to donate $25,000 to the City of Jefferson under two conditions. First of all, Carnegie wanted the city to purchase on its own a suitable site for the library. Secondly, he wanted the city council to “obligate itself by resolution to expend the sum of three thousand dollars annually, to maintain the library….”

Hendy and Hough were disappointed with Carnegie’s response. They feared that the city council would not commit to spending $3.000 annually to maintain the library. Thus, the two of them traveled to New York, hoping for a personal audience with Carnegie so that they might try to persuade him to reduce the annual commitment to be made by the city. Unable to meet with Carnegie, the men were told by his secretary that the philanthropist would be unyielding and that if the community would not spend $3,000 of the city money for the library’s maintenance, Carnegie would give nothing to the project.

Hendy and Hough returned to Jefferson City and lobbied the city council to commit the funds in accordance with Carnegie’s wishes. The city council decided to propose a tax of one mill on every dollar of assessed valuation, with the money raised to be used for the library maintenance fund. On June 19, 1900, Jefferson City residents went to the polls to vote on this proposition. They approved it overwhelmingly by a vote of 839-42.

Two weeks later, on July 2, 1900, the city council voted to set aside $3,000 for annual library maintenance and began the search for a suitable site. Local property owners offered 15 different sites for the library. Fred Binder, a local contractor, offered to donate a lot for the library site, but the land he offered was at the corner of Madison and Dunklin streets, on the city’s south side. The library’s board of directors wanted to build the library closer to the downtown area. The site chosen was at the southeast corner of Madison and McCarty streets. The owners of the land, however, wanted $6,000. The library board tried to raise the money by “private subscription” but failed. A cheaper site had to be found.

Ultimately, the site selected was in the 200-block of Adams Street. It was owned by Dr. I, N. Enole and Thomas F. Roach who were willing to sell the property for $4,350. Eventually, the selling price was lowered to $3,600, the money was raised, and the land was purchased. Meanwhile, on August 4, 1900, Carnegie wrote to give approval to the library board’s plan and authorized the construction to begin.

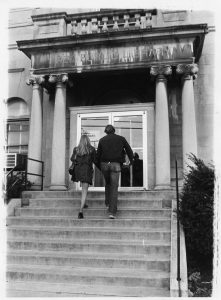

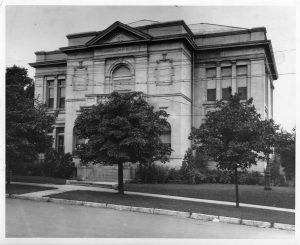

The board of directors solicited plans for the building. The Jefferson City architectural firm of Miller & Opel submitted the winning design. They proposed a building that would be “classical in style,” extending 66 feet along Adams Street on the front and 78 feet back along the alley that bisected the block between High Street and modern-day Capitol Avenue.

Bids for construction of the library were sought soon after. Henry J. Wallau was awarded the construction contract after submitting the lowest bid of $21,500. Wallau was allowed an additional $150 for the removal of an “old building” that stood on the construction site. Wallau agreed to complete the building by February 1, 1902, and to use” Cole County limestone… in the construction of the foundation while Carthage and Blue Bedford stones will be used in the upper story.” The heating system was to be installed by Jefferson Heating Company, headed by Ernest Simonsen, a prominent local businessman for whom the ninth grade public school building on Miller Street is named.

There were multiple delays in the construction of the new library, including one caused by a shortage of available Cole County limestone – eventually Blue Bedford stone was used as a substitute. A severe winter in 1900 and a hod-carriers’ strike in the fall of 1901 also slowed construction. As a consequence, the completion of the building was delayed by more than ten months.

1902: Dedication

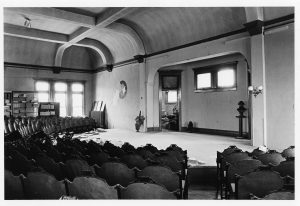

The Carnegie Free Public Library of Jefferson City was formally dedicated on December 23, 1902. Hundreds of local citizens came out for the 8:00 P.M. ceremony, held in the library auditorium. The auditorium had been added, with Carnegie’s approval, “for literary and educational purposes” and had a seating capacity of approximately 450 people.

Local businessman Huge Stephens delivered the keynote address at the gathering (A year later, Stephens would be involved in an effort to get the library to stop using soft coal because “of the great amount of soot thrown out from the Library furnace. It is a menace to the cleanliness and comfort of our homes”). Music for the dedication was provided by a chorale group known as the St. Cecilia Club and by the Jefferson City Orchestra. Library board president Arthur M. Hough presented the building to Mayor A. C. Shoup, and the library became part of the city’s cultural and educational landscape.

1902 – : Expansion and renaming

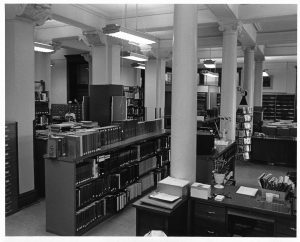

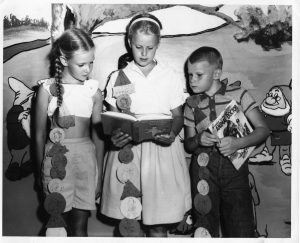

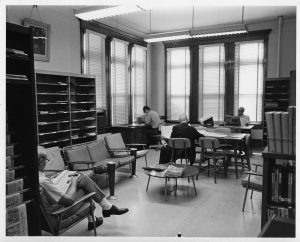

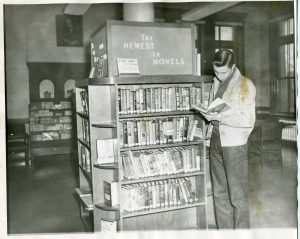

The library was open to the public from 9:00 A.M. to 9:00 P.M. Monday through Saturday. Sunday hours were 2:00-5:00. Residents of the city “over the age of nine years” could use the library free of charge. County residents were required to pay a two-dollar annual fee. Among the rules of the library was the following: “The use of tobacco, all conversation and other conduct not consistent with the quiet and orderly use of the reading room are prohibited.”

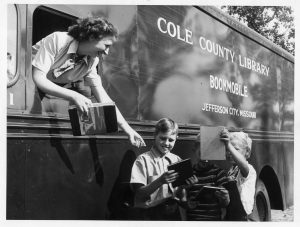

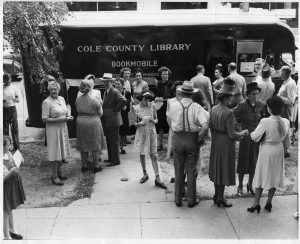

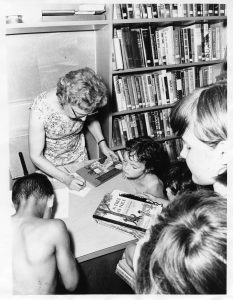

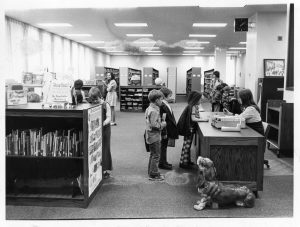

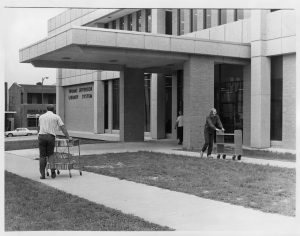

The Carnegie Library became a county library in 1947, the same year that the popular “Bookmobile” program was established. The original Carnegie Library was replaced by the Thomas Jefferson Library building, located at the corner of High and Adams streets, which has been known since 1994 as the Missouri River Regional Library.

This article by Gary Kremer was originally featured in the Jefferson City News Tribune on July 15, 2000. It was subsequently included in Volume I of Heartland History: Essays on the Cultural Heritage of the Central Missouri Region by Gary Kremer. Photos are from the Missouri River Regional Library archives.